I recently read an American Educator article from 2012 by Barak Rosenshine that set out 10 principles of instruction informed by research, with subsequent suggestions for implementing them in the classroom. It was also one of the articles cited in the “What makes great teaching? Review of the underpinning research” by Rob Coe et al and provided further elaboration on one of their six components of great teaching thought to have strong evidence of impact on student outcomes, i.e. quality of instruction.

Here’s my summary of the key messages from each of the 10 principles.

1: Begin with a short review of prior learning

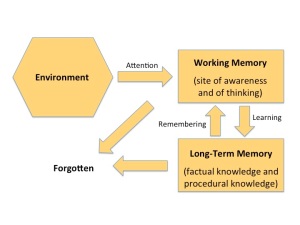

Students in experimental classes where daily review was used had higher achievement scores. A 5-8 minute review of prior learning was said to strengthen connections between material learned and improve recall so that it became effortless and automatic, thus freeing up working memory.

Daily review could include, for example:

- Homework

- Previous material

- Key vocabulary

- Problems where there were errors

- Further practise of knowledge, concepts and skills

2: Present new material in small amounts or steps

Working memory is small and can only cope with small chunks at a time. Too much information presented at once overloads it and can confuse students, who won’t be able to process it. Sufficient time needs to be allocated to processes that will allow students to work with confidence independently. More effective teachers in the study dealt with the limitation of working memory by presenting only small amounts of new material at a time.

3: Ask a large number of questions and check the responses of all students

Questions allow students to practise new material and connect new material to prior learning. They also help teachers to determine how well material has been learned and whether additional teaching is required. The most effective teachers asked students to explain the process they used and how they answered the question, as well as answering the question posed.

Strategies suggested for checking the responses of all students included asking students to:

- Tell their answers to a partner

- Write a short summary and share it with a partner

- Write their answers on a mini-white board or similar, followed by “show me”

- Raise their hands if they know the answer or agree with someone else

4: Provide models

Students require cognitive support to reduce the cognitive load on their working memory and help them to solve problems faster. Examples include:

Students require cognitive support to reduce the cognitive load on their working memory and help them to solve problems faster. Examples include:

- Providing clearly laid out, step-by-step worked examples

- Identifying and explaining the underlying principles of each step

- Modelling the use of prompts

- Working together with students on tasks

- Providing partially completed problems

5: Guide student practice

New material will quickly be forgotten without sufficient rehearsal. Rehearsal helps students to access information quickly and easily when required. Additional time needs to be spent by students summarising, rephrasing or elaborating on new material so that it can become:

New material will quickly be forgotten without sufficient rehearsal. Rehearsal helps students to access information quickly and easily when required. Additional time needs to be spent by students summarising, rephrasing or elaborating on new material so that it can become:

- Stored in long-term memory

- Easily retrieved

- Used for new learning and problem solving

The quality of storage relies on:

- Student engagement with the material

- Providing feedback to the students to correct errors and ensure misconceptions aren’t stored

The rehearsal process can be facilitated and enhanced by:

- Questioning students

- Asking students to summarise the main points

- Supervising students during practice

In one study, the more successful teachers spent more time guiding practice, for example by working through initial problems at the board whilst explaining the reasons for each step or asking students to work out problems at the board and discuss their procedures. This also served as a way of providing multiple models for students to allow them to be better prepared for independent work.

6: Check for student understanding

More effective teachers frequently checked for understanding. Checking for understanding identifies whether students are developing misconceptions as well as providing some of the processing required to move new learning into long-term memory.

The purpose of checking is twofold:

- Answering questions might cause students to elaborate and strengthen connections to prior learning in their long term-memory

- The answers provided by students alert the teacher to parts of the material that may need reteaching

A number of strategies can be used to check for understanding, e.g:

- Questioning

- Asking students to think aloud as they work

- Asking students to defend a position to others

7: Obtain a high success rate

When students learn new material, they construct meaning in their long-term memory. Errors can be made though, as they attempt to be logical in areas where their background knowledge may still be weak. It was suggested that the optimal success rate for fostering student achievement is approximately 80%. Furthermore, it was said that achieving a success rate of 80% showed that students were learning the material, whilst being suitably challenged. High success rates during guided practice led to higher success rates during independent work. If practice did not have a high success rate, there was a chance that errors were being practised and learned, which then become difficult to overcome. The development of misconceptions can be limited by breaking material down into small steps, providing guided practice and checking for understanding.

When students learn new material, they construct meaning in their long-term memory. Errors can be made though, as they attempt to be logical in areas where their background knowledge may still be weak. It was suggested that the optimal success rate for fostering student achievement is approximately 80%. Furthermore, it was said that achieving a success rate of 80% showed that students were learning the material, whilst being suitably challenged. High success rates during guided practice led to higher success rates during independent work. If practice did not have a high success rate, there was a chance that errors were being practised and learned, which then become difficult to overcome. The development of misconceptions can be limited by breaking material down into small steps, providing guided practice and checking for understanding.

8: Provide scaffolds for difficult tasks

Scaffolds are temporary supports that help students to learn difficult tasks, which are gradually withdrawn with increasing competence. The use of scaffolds and models, aided by a master, helps students to serve their “cognitive apprenticeship” and learn strategies that allow them to become independent.

Scaffolds are temporary supports that help students to learn difficult tasks, which are gradually withdrawn with increasing competence. The use of scaffolds and models, aided by a master, helps students to serve their “cognitive apprenticeship” and learn strategies that allow them to become independent.

Scaffolds include:

- Thinking aloud by the teacher to reveal the thought processes of an expert and provide mental labels during problem solving

- Providing poor examples to correct, as well as expert models

- Tools such as cue cards or checklists

- Prompts such as “Who?” “Why?” and “How? that enable students to ask questions as they work

- Box prompts to categorise and elaborate on the main ideas

- A model of the completed task for students to compare their own work to

9: Require and monitor independent practice

Independent practice follows guided practice and involves students working alone and practising new material. Sufficient practice is necessary for students to become fluent and automatic. This avoids overcrowding working memory, and enables more attention to be devoted to comprehension and application.

Independent practice follows guided practice and involves students working alone and practising new material. Sufficient practice is necessary for students to become fluent and automatic. This avoids overcrowding working memory, and enables more attention to be devoted to comprehension and application.

Independent practice should involve the same material as guided practice, or with only slight variation. The research showed that optimal teacher-student contact time during supervision was 30 seconds or less, with longer explanations being required an indication that students were practising errors.

10: Engage students in weekly and monthly review

As students rehearse and review information, connections between ideas in long-term memory are strengthened. The more information is reviewed, the stronger these connections become. This also makes it easier to learn new information, as prior knowledge becomes more readily available for use. It also frees up space in working memory, as knowledge is organised into larger, better-connected patterns.

As students rehearse and review information, connections between ideas in long-term memory are strengthened. The more information is reviewed, the stronger these connections become. This also makes it easier to learn new information, as prior knowledge becomes more readily available for use. It also frees up space in working memory, as knowledge is organised into larger, better-connected patterns.

Practical suggestions for implementation include:

- Review the previous week’s work at the beginning of the following week

- Review the previous month’s work at the beginning of every fourth week

- Test following a review

- Weekly quizzes

The full report by Barak Rosenshine: Principles of Instruction – Research based strategies that all teachers should know is available here.