This post is part of an ongoing series written by our PBL Lead Laura Jackson, about how we are implementing R.E.A.L. Projects in school.

As I said when I ended my previous post, I feel very excited when I see the staff project folders with exciting projects in them. There is a summary of all of these at the end of this post and I’m sure you’ll agree that these projects will give our students an exciting variety of different learning experiences during our projects week. I think it’s important to detail how we got to this place in such a short space of time.

Back in February, all staff spent time with our PBL coach, Cara, planting “seeds of passion”- to try to find a way to ignite little sparks of exciting energy to then develop and create into Rigorous, Engaging, Authentic Learning experiences.

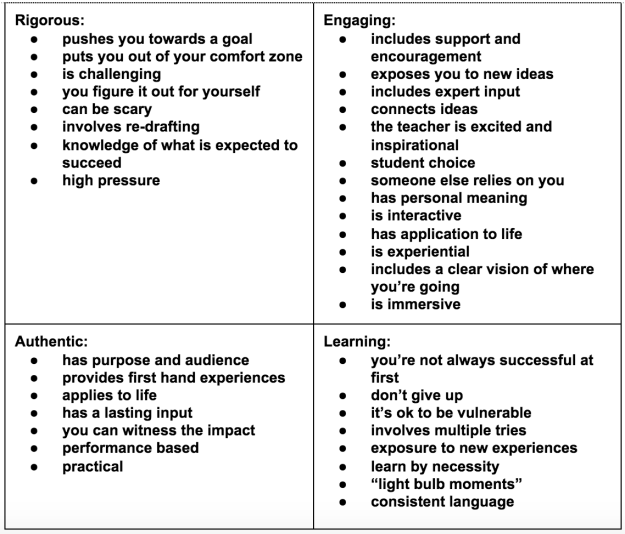

These words are vital but how can we apply rigour? How can we ensure projects are engaging? How can authenticity be validated? All of these need to be encapsulated within a learning experience. What do they actually mean? How do we do it?

The Innovation Unit says:

We also had to decide how to assess each project and also projects had to be “tuned” to make sure they had been given critique, and that and questions the project leader or the critique group may have had about the project were acknowledged and addressed if needed.

Project Tuning

One of the most important parts of project work is the giving and receiving of critique. This happens at all stages of the project but the earliest stage would be at the “tuning” stage. This was also possibly the most challenging part to co-ordinate from my point of view as each project needed to be tuned but also as part of a group, who would be the critique providers.

In preparation for this, Curriculum Leaders took part in a Critique and Tuning workshop with Cara to allow them to take this process into their Project groups. I then led a critique workshop for the rest of the staff which ensured we all felt it. If you have an emotional connection with something then you feel more passionate about it and believe in it more. If people start changing things, adding bits, taking bits away then it changes YOUR work and YOUR emotional connection with the work.

It was important to me that all staff took part in this session and it was also a light-hearted way to introduce critique to staff, but with a serious message. If critique is given in the wrong way to anyone- staff creating, developing or delivering the project or students who are completing the project, then this would not be useful to anyone and would have a detrimental effect on the person receiving the critique. As adults, we are very protective of our own ideas and values and if they are questioned in the wrong way then it becomes a negative experience and this should not be the case. This is also true of our students we work with day-to-day. This task made me think about how we self and peer critique in lessons and I intend to use the same session with students towards the end of the academic year, time willing.

Working with Cara has also introduced me to a fantastic book- The Power of Protocols which is extremely useful in terms of gaining the maximum usage out of a set amount of time. This way of working was also used in a session I attended at School 21 in February when we were discussing enabling conditions for projects in schools. Although I first thought using protocols seemed very regimented, I quickly realised that having set times for different parts of discussion, meeting and critique work is actually extremely useful and stops a lot of time being wasted just chatting or wandering off topic.

To tune projects, there is a need to be very specific and concise to articulate the project to others. In the protocol there are also “norms”

- Hard on the content, soft on the people,

- Share the air (or “step up, step back”)

- Be kind, specific and helpful

This allows all the conversation and discussion taking place to be focused solely on the project and the content.

Within the tuning protocol, there are also different roles :

- Facilitator -Begins the session by reading through the protocol. During the protocol, the facilitator is responsible for keeping the discussion on point and reminding participants to adhere to the norms.

- Timekeeper– Keeps time for each section and lets the facilitator know when time is up.

- Presenter – Shares his/her work with the group.

- Critical Friends – Includes all people present except for the presenter.

During the tuning process, the presenter gets time to present their project idea and the area or aspect they would like critique on. The critical friends then ask clarifying questions to gain a deeper understanding of any aspect of the project or specific area. The critical friends then discuss the project with the presenter taking notes on their discussion without being involved and then they respond to this discussion at the end. The response could take the form of addressing some of the issues discussed by others, drawing conclusions from what has been said or discussed or simply acknowledging the points made by others. The facilitator introduces each part of the protocol and the timekeeper ensures the protocol timings are adhered to. Timings may differ depending on time constraints- we tuned projects in 15 minute blocks (2 mins- 3 mins- 8 mins- 2 mins) but clearly timings and therefore the timings within each part of the protocol can be changed as needed.

Project Assessment

As well as tuning our projects, we also needed to decide on how our projects would be assessed.

“Academic rigour- head, hand and heart” was my message from the School 21 retreat. Within our discussions in school also, the learning that would take place during the week needed to be meaningful, exciting and also rigorous. The word rigour again:

The Innovation Unit use Buck Institute for Education’s “21st Century Skills” framework to assess PBL work. The Buck Institute website contains a myriad of resources, ideas and information about PBL from all over the world and contains some fascinating work and reading. Their twitter account is definitely worth a follow.

We focused on:

ICT Literacy

- how to find information

- how to use equipment

Cognitive Skills

- Critical Thinking

- Creative Thinking

Metacognitive Skills

- Self- management

- Reflection

Personal Characteristics

- Risk Taking

- Accountability

Interpersonal Skills

- Communication

- Collaboration

As Curriculum Leaders, we discussed our projects with one another and looked for assessment opportunities within these discussions. Once we had these then we put them into the categories above, to allow us to see where the most likely assessment opportunities lay in our range of projects.

From this we then decided on three assessment strands which would be able to be assessed in any project taking place. We also added a learning target to each one to show what would need to be achieved in each assessment strand.

Communication – I can communicate my learning to others in an appropriate way.

Gathering Information – I can source, locate and investigate appropriate information using ICT.

Cognitive Skills – I can reflect and adapt to overcome challenges in my learning.

After further discussion with Cara on a different day, we also decided that to assess all three in one week would be very difficult, especially because critique could lead to multiple drafts. It could also potentially dilute the quality of assessment and critique in the project. Only one strand will be assessed in each project and this is to be decided by the project delivery staff on each project. This is another benefit of using Cara’s expertise as she works in this field and has experience in this area- I, and we, are still developing our skills all the time and this small tweak means that time will be used effectively and assessment will still be rigorous which is what we require.

From this, short term learning targets have been created within the project plans to individualise the learning target for the projects.

Finally, I would also like to share the variety of projects staff have created and the essential questions driving the projects.

| Project Title | Essential Questions |

| Would you feed your hungry neighbour? |

|

| Zombie Apocalypse |

|

| Flotsam and Jetsam |

|

| Orienteering in the local community |

|

| Mood Music |

|

| Travel Tracks |

|

| Maths Movie Making (M3) |

|

| Afternoon Tea |

|

| Community |

|

| Set, Props and Costume |

|

| Does Fashion have a price? |

|

| When in Rome… |

|

| Vikings |

|

| Durham Cathedral through your own eyes |

|

| Kidz for Kidz |

|

| Films |

|

| Rock Climbing |

|

| Seaham |

|

| Science: Great Beauty or Horrifying Monster? |

|

| 21st Century Britain |

|

| Trashion |

|

I intend to create a daily diary blog during our Projects Week – 29th June 2015 to document the week as it happens.